![]()

Expand your knowledge and techniques as a practitioner of the occult.

In the interest of full disclosure, please know that I myself do not practice any occult, esoteric, or religious practices. My hope is that I will eventually add information from contributors to this site who are active practitioners as well as cultivate conversation in the forum. However, until that stage of the project is underway, I believe I have enough academic experience and knowledge to assist those who are both casually interested in the occult as well as seasoned practitioners. I do my best to delineate where my insight changes from researched facts and accepted history to my own interpretations or opinions. I am fallible so please feel free to contact me if you need clarification on a topic, you disagree with something I have written, or if I flat-out got something wrong. It happens sometimes and I welcome outside input (especially from practitioners).

Also, because I myself find this important when commenting on certain topics as well as it being an increasingly common talking point in the current culture, I want to let my readers know that I am a white, American, queer individual (they/them). I am aware that anything I say about practices that come from cultures that are not my own as well as the experiences of people of color are not authoritative. I know that I will make mistakes in this area but I want to learn and get better. For my readers of color, I humbly ask that you accept my deference to you in these areas and that I supply the information and opinions I do as respectfully as possible in the interest of expressing as full a range of practices as possible. In addition, though I can personally reflect on LGBTQ+ elements of the occult and supply an individualized perspective, I do not speak for all LGBTQ+ people. My experience and identity as a queer person do not encompass the diverse experiences of the entire community. I will say that I can comment as a part of that community. Questions, comments, angry rants, can call be sent to: digitaloccultlibrary@gmail.com

With that out of the way, let’s start with a few guiding questions:

What is your occult heritage?

This is why I had the long preface at the start. In my experience, most people interested in the occult and esoteric feel the urge to explore traditions they are connected to by way of their ancestry. Damien Echols, who has explored a wide variety of practices, comments that he felt more comfortable with western esoteric traditions despite respecting and studying eastern philosophies in an episode of The Midnight Gospel (and the related podcast episode; click on the page for context and more information). Since Echols was born and raised in Arkansas, his cultural worldview was built on a Christian scaffold regardless of his religiosity. How and why major religions shape individual perspective is a topic that could fill volumes. My point for now is just to recognize that people tend to favor what they’re already familiar with.

In contrast, sometimes exploring a vastly different perspective and culture can be liberating. Just because you were raised in a culture doesn’t guarantee that you feel comfortable in and accepted by it. Occult and esoteric traditions are by their nature and definition outliers. People who feel ostracized or alienated by the mainstream religion or culture will naturally gravitate to these practices. I believe this is why there is a noticeable prevalence of LGBTQ+ practitioners. When mainstream religion actively condemns you, why not seek spirituality elsewhere? Women, likewise marginalized and disenfranchised, find power and expression through Wicca and witchcraft.

![]()

If you’re still lost, I recommend that you start with your own background and see what resonates with you. You don’t have to “try it out” first; I just mean that if you don’t know where to start your research it is as good a place as any. Most of what is currently on this site is based in Western esoteric traditions. You’ll find that the Middle East, including Arabic, Persian, Judaic, Turkish, and other nearby cultures, had a massive impact on the occult in roughly the 9th to 13th centuries. So, if that is your own background you’ll find a lot of overlap there. Judaism of course has its own rich and massive esoteric traditions, Kabbalah being only one of them (though probably the largest and most complex). Literally thousands of years has produced elegant and complex systems that would take more than a lifetime to fully understand. Judaism is also rare in that it is a demonstrably unbroken line of practice. While other traditions may claim this, historically speaking there is little evidence for most of them. So, if you are Jewish you have quite a large tradition naturally open to you.

Wicca is a common go-to for people with European backgrounds. This is one of those aforementioned traditions that claims an unbroken lineage. However, outside of a few areas where folk traditions described as “witchcraft” have been continually passed down through generations, modern Wicca and witchcraft are reconstructions popularized by Gerald Gardner in the early 20th century. This doesn’t make the practices any less valid but practitioners should be aware of the genuine origins despite enticing propaganda. Related practices like paganism, neo-paganism, druidry, heathenry, Goddess worship, and other new religious movements are similar in that they attempt to recreate practices from a time before Christianity essentially dominated and replaced them. The traditions that they draw from, however, were characterized by lacking written records to draw on. There is no “Druid Bible” that has been preserved and passed down for two thousand years that tells you how to be a druid. What we have are archeological evidence and, rarely, tangental written records that describe practices and rituals (often from an outside, biased perspective). Obviously each of these will have their own history and background, some with better precedent and records than others. Again, this doesn’t invalidate the practice, but please be wary of anyone claiming absolute “ancient authority”. Esoteric and occult traditions thrive on individualism and thinking for yourself. You don’t need someone else to tell you secrets when you’re free to discover them for yourself.

Scholar Stefanie von Schnurbein quotes a practitioner of Heathenism in her book, Norse Revival: Transformations of Germanic Neopaganism, who expresses a typical relationship practitioners have with these types of recreated, neopagan religions rather beautifully:

Rituals are the traditional core of Heathenism. It is not a dogmatic religion that places the belief in its teachings in the center, but a living relationship to the gods, to nature and to everything holy that realizes itself actively. It is not theory, but practice. Being a Heathen means to practice Heathenism.

(translated from German by Schnurbein; see page 106 of Norse Revival)

I read this quote after I had decided to refer to “practitioners” as such on this site. I feel that this sentiment is what characterizes occult and esoteric belief in a way that doesn’t apply the same way to mainstream religions. Religions demand belief and often participation but esoteric traditions, while certainly having their own theology and theory, put praxis front and center.

![]()

Unfortunately, anyone exploring or drawn to these modern pagan styled practices need to be aware of an unfortunate reality. While white national and neo-nazi sentiments are in no way the majority or foundation of Germanic and Scandinavian pagan revivals, there are individuals and small groups that adopt symbols, rhetoric, and proclaim to be practitioners of these revivals. Just because these abhorrent people have latched on to them does not mean that you can’t explore or practice them yourself. However, please be extremely cautious when doing so. It is common for hate groups to start with “reasonable” sounding rhetoric, such as “aren’t you proud of your heritage?”, to entice and manipulate others into adopting their loathsome views. There is a huge jump from respecting a culture, and being proud to be a part of it, to claiming its superiority over others. As such, any hateful, racist, or related comments and speech will absolutely not be tolerated by me in my curated space. It is perfectly fine to have questions; I have many in regards to cultures I am unfamiliar with. It is not acceptable to be hateful or disparaging toward them. Racism is an ongoing issue and conversation (recent events have made that devastatingly clear). As I said in my disclaimer above, I am not right all the time and I expect to make mistakes. The same goes for my readers. This is a difficult topic but one we shouldn’t shy away from. As always, questions, comments, and counter-arguments are welcome at digitaloccultlibrary@gmail.com

Some of the more recent, notable movements in Western occultism are those surrounding Satanism. The two most prominent organized Satanic groups are “The Church of Satan“, founded in 1966 by Anton LaVey, and “The Satanic Temple“, co-founded by Lucien Greaves and Malcolm Jarry in 2013. There are other movements and belief systems that are described as “Satanism” that worship Satan as a deity, but neither “The Church of Satan” nor “The Satanic Temple” profess belief of a literal Satan. Both use Satan as a symbol for rebellion and individualism. Their respective official websites offer more in the way of details on their tenets and history, but some of the key differences between them. The Church of Satan focuses more on ritual magic and uses the writings of the late Anton LaVey as a guide. In contrast, The Satanic Temple has no official books or literature, instead adhering to a few basic tenets. While they entertain some rituals based on feelings of personal liberation, they officially denounce the overtly magical and superstitious aspects found in LaVeyan Satanism. The Satanic Temple is highly politically active, advocating for reproductive rights and the protection of children among other causes related to social justice, rights, and liberties. The Church of Satan’s members describe themselves as atheists who do not worship the devil while The Satanic Temple advocates for agnosticism among members as well as the separation of superstition from religion. The Church of Satan has been accused of advocating for elitist and even fascist views, stemming from its founder’s misanthropic distaste for what he considered “human nature”. I am not advocating for either organization, just informing those who are interested in what forms modern occultism has taken. Both organizations have FAQ pages which both dispel popular misunderstandings as well as inform on their individual philosophies:

I won’t comment on any non-western belief systems until I am more educated in them. This page is already too long. If anyone is interested in more information, clarification, or suggestions, drop by the forum here or send me an email: digitaloccultlibrary@gmail.com

What is your goal as a practitioner?

Knowledge? Power? Self empowerment or understanding? Connecting with something greater than yourself?

Do you believe in God, gods, angels, or other supernatural powers? Do you believe in magic?

What got you interested in the occult, esoteric, or other non-traditional practices? What did you find appealing? What spoke to you about it? What need did it fill?

What do you want to learn and how do you want to grow? Do you want to practice alone? Are you craving a group to learn from and practice with?

Do you want to find an established system or make up your own rules and rituals? Do you want to practice “white” magic or does your heart wish to indulge in “black” magic?

Will you take the Left Hand Path or the Right Hand Path?

These are all good questions to workshop when exploring your practice. I can’t offer all the possible answers for you here, but take a look at a few pages on the site that may help:

Foucault’s Pendulum (a must read for all occultists)

I would also recommend The New Encyclopedia of the Occult by John Michael Greer as a general reference guide for practitioners. He is himself a practitioner but takes a noticeably academic view in terms of history and research (see the “Special Note” below for why I consider that important). Secrets of the Magical Grimoires by Aaron Leitch is another example of a good balance between practice and scholarship. Secrets is geared specifically toward the Western traditions through the eponymous Grimoires. It also puts the practices and primary sources in a historical context which aids in understanding them.

A Special Note For Practitioners:

I’ve said before that I myself am not a practitioner, I consider myself an academic or scholar, yet hold high regard for those who practice what I study. If I am able to pass along one piece of advice to practitioners that I have learned from academics, it is to always dig deep into your sources. Never take anything at face value. This doesn’t mean that you can’t accept or believe whatever you decide on; this is not an appeal to pure reason at the expense of spirituality. My advice is simply a reflection on the mundane fallibility of humans.

With the advent of online resources, whether it be websites, digitized books and manuscripts, blogs, etc., the occult has become much more accessible. The internet is a tool that is only good or bad depending on how you use it and as such this accessibility is both a gift and a curse. A large part of the intention of esoteric philosophy’s obscure, coded, and hidden nature is intentional. Masters and practitioners thought that their knowledge was too powerful or too complicated for the general populace and was thus prime for misuse and misunderstanding. As such, aggregating occult and esoteric content without the proper guidance or context can be misleading at best or dangerous at worst. On a practical level, something as seemingly innocuous as making tea from herbs you read about on a blog can cause serious harm or death if the name is slightly wrong. In terms of metaphysical practice, information copied and pasted anonymously may be based on a mistranslation, typo, or have dubious providence. Much of the information readily available online are from public domain works from the turn of the century or earlier. Often these works don’t have a high standard of research, translation, or are biased toward the cultural standards of bygone eras. For example, An Encyclopaedia of Occultism by the Scottish folklorist and scholar Lewis Spence is readily available from numerous sources, one example found here at Archive.org:

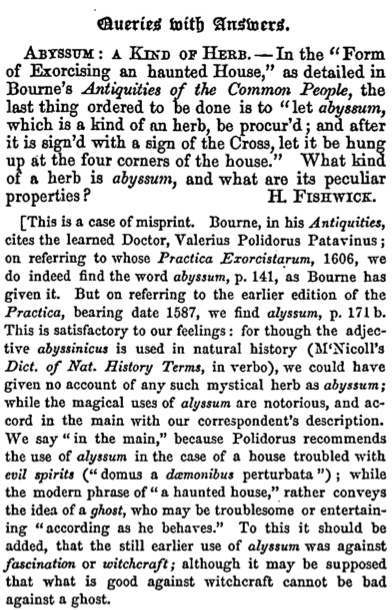

Both the description as an “encyclopedia” as well as the author’s academic status would imply it was an accurate resource. On the second page, however, there is an entry for “Abyssum”, described as follows: “A herb used in the ceremony of exorcising a haunted house. It is signed with the sign of the cross, and hung up at the four corners of the house.” I had been browsing through various sources I had found online and this stuck out to me. I decided to dig a little deeper because I had never heard of such an herb (although not being a botanist or this isn’t unusual). It turns out I didn’t have to search very long before I found the following (a picture of the relevant excerpt followed by the citation):

Abyssum: A Kind of Herb, Notes and Queries, Volume s3-VIII, Issue 199, 21 October 1865, Pages 334–335, https://doi.org/10.1093/nq/s3-VIII.199.334c

This was published in 1865, decades before Spence’s encyclopedia. It describes a misprint of “alyssum” to “abyssum” between editions of a 16th century book. I don’t point this out to disparage the late scholar; he obviously didn’t have the resources that we have now. He probably would have been incredulous at the idea that it took me ten minutes to do the same research that, in his time, hours of scouring publications in a university library may not even accomplish. This tiny example, a few lines from an obscure encyclopedia, shows not only the power we now have at our literal fingertips but also the difficulty in parsing so much information.

I don’t expect practitioners to scour every reference with the zeal of a pedantic scholar (that’s my job). All I want is to make practitioners aware of the different types of information available and how to responsibly use them. The most difficult part of creating this site has been going over so much information and trying my best to represent it as genuinely as possible. I’m sure that I’ve made mistakes but that’s ok. Just as occultism is a living art, so too is scholarship in its way. We all learn and discover more through our craft every day. This process allows us to apply what we learn in new, thoughtful ways. There is no shame in ignorance, only in willful ignorance.

There is a reason wise sages and teachers are generally depicted as old and gray; this kind of skill takes a long, long time to develop and there are no shortcuts. So enjoy it. Revel in new discoveries. Look forward to learning something new. Don’t be afraid to ask questions. Continue to seek out that which is hidden with joy and anticipation.

![]()

Bibliography and Works Cited

“Abyssum.” Spence, Lewis. An Encyclopaedia of Occultism, London, George Routledge & Sons, p. 2. https://archive.org/details/encyclopaediaofo1920spen/page/2/mode/2up.

“Abyssum: A Kind of Herb.” Notes and Queries, Volume s3-VIII, Issue 199, 21 October 1865, Pages 334–335, https://doi.org/10.1093/nq/s3-VIII.199.334c

Copenhaver, Brian P. The Book of Magic: from Antiquity to the Enlightenment. Penguin Classics, 2016.

Faivre, Antoine, and Karen-Claire Voss. “Western Esotericism and the Science of Religions.” Numen, vol. 42, no. 1, 1995, pp. 48–77. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3270279.

Greer, John Michael. The New Enclycopedia of the Occult, Llewellyn Publications, 2003.

LaVey, Anton. The Satanic Bible, Avon Books, 1969.

Leitch, Aaron. The Secrets of the Magical Grimoires, Llewellyn Publications, 2011.

Levack, Brian P., editor. The Witchcraft Sourcebook. Routledge, 2004.

Partridge, Christopher, editor. The Occult World. Routledge, 2016.

Schnurbein, Stefanie von. Norse Revival: Transformations of Germanic Neopaganism, Brill, 2016.