What constitutes “witchcraft” and how its practitioners have been viewed throughout the centuries in the western world has changed dramatically. From folk practices, to church hysteria and persecution, to female empowerment, the term “witch” evokes a long and sordid history.

Etymology

In fact, even the word “witch” is distinct from the underlying practice of “witchcraft”. The general definition of witchcraft is the practice of magic in a negative or harmful fashion (whatever that may mean at the point in history you’re looking at). Where a source may refer to a sorceress, medium, or wizard, more recent translations will use the term “witch”. For example, the figure popularly known as “The Witch of Endor” from the first book of Samuel is actually called a “medium”, or one who speaks with the dead. This act was forbidden and so to express that what she did was taboo, she is commonly referred to as a “witch”. (1 Samuel 28) The word “witch” specifically has Anglo-Saxon origins. The earliest instance I could find in my research was in the form of the word “wiccan” from “The Law-Code of King Alfred the Great” in which it was quoting Exodus 22:18. The New Oxford Annotated Bible translates it as follows:

You shall not permit a female sorcerer to live.

The Laws of Alfred (as it is also known, as well as “The Doom Book”) translates “female sorcerer” as “wiccan”. (see the Bibliography below for full citations) This eventually evolved into the Middle English “wicche” and by the 16th has the modern spelling, “witch”. The exact etymology of the word is unknown, especially its earliest origins, but that is the general outline of how we got the word “witch” in modern English.

So, if you see the word “witch” used before the 16th century, it’s probably a translation of “sorceress”, “wizard”, “medium”, or something similar. I know this all seems unreasonably pedantic, but it does make a difference in understanding the actual history. The word “wiccan”, though it appeared as early as the 800s in Anglo-Saxon, wasn’t used to refer to Wicca until Gerald Gardner used it to describe his supposed time with the New Forest coven in 1939. The relationship between “witchcraft” and “Wicca” only gets more complicated from here.

History

Witch-like figures in early history and literature abound. The Witch of Endor from the Bible, Circe from the Odyssey, Morgan le Fay of Arthurian myth, Prospero and the Weird Sisters from Shakespeare are among the most prominent. Sorcerers, oracles, mediums, and other practitioners of magic were feared and revered in equal measure. Once Christianity began to dominate the western world, however, such magic became associated with the devil. Active persecution, trials, and executions of accused witches (both men and women) occurred in the Middle Ages but reached their peak in the Renaissance. From approximately 1300 to 1700, when superstition began to be questioned within the culture as a whole, estimates as to the number of people killed for the crime of witchcraft range from 100,000 to 300,00 across Europe. A papal bull issued in 1484 by Pope Innocent VIII, titled Summis desiderantes, formalized the Catholic Church’s belief in and persecution of witches and witchcraft. The charges against these supposed witches are described:

It has recently come to our ears, not without great pain to us, that in some parts of upper Germany, as well as in the provinces, cities, territories, regions, and dioceses of Mainz, Ko1n, Trier, Salzburg, and Bremen, many persons of both sexes, heedless of their own salvation and forsaking the catholic faith, give themselves over to devils male and female, and by their incantations, charms, and conjurings, and by other abominable superstitions and sortileges, offences, crimes, and misdeeds, ruin and cause to perish the offspring of women, the foal of animals, the products of the earth, the grapes of vines, and the fruits of trees, as well as men and women, cattle and flocks and herds and animals of every kind, vineyards also and orchards, meadows, pastures, harvests, grains and other fruits of the earth; that they afflict and torture with dire pains and anguish, both internal and external, these men, women, cattle, flocks, herds, and animals, and hinder men from begetting and women from conceiving, and prevent all consummation of marriage; that, moreover, they deny with sacrilegious lips the faith they received in holy baptism; and that, at the instigation of the enemy of mankind, they do not fear to commit and perpetrate many other abominable offences and crimes, at the risk of their own souls, to the insult of the divine majesty and to the pernicious example and scandal of multitudes.

The bull goes on to give authority to inquisitors to arrest, imprison, question, and execute whoever they see fit:

We therefore, desiring, as is our duty, to remove all impediments by which in any way the said inquisitors are hindered in the exercise of their office, and to prevent the taint of heretical pravity and of other like evils from spreading their infection to the ruin of others who are innocent, the zeal of religion especially impelling us, in order that the provinces, cities, dioceses, territories, and places aforesaid in the said parts of upper Germany may not be deprived of the office of inquisition which is their due, do hereby decree, by virtue of our apostolic authority, that it shall be permitted to the said inquisitors in these regions to exercise their office of inquisition and to proceed to the correction, imprisonment, and punishment of the aforesaid persons for their said offences and crimes, in all respects and altogether precisely as if the provinces, cities, territories, places, persons, and offences aforesaid were expressly named in the said letter.

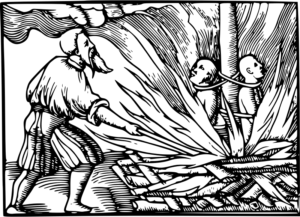

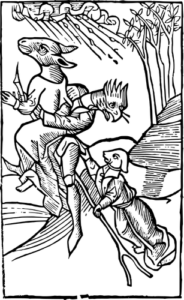

Formal Inquisitions were headed by the Catholic Church to root out “heresy” in many forms, not just witchcraft. This bull, however, was in response to a German inquisitor who was particularly obsessed with punishing witches. This inquisitor, Heinrich Kramer, included a copy of the bull in the front of his treatise on witches and witchcraft, the Malleus malefucarum, published in 1486. Known as “The Hammer of Witches”, this book proved to be devastatingly influential and cost many innocent people their lives throughout Europe during the Renaissance. Accused witches were not just painfully executed, they were first subject to torture and interrogation as outlined by Kramer. There was no reprieve for the accused; most gave in under the horrendous pain of torture and falsely confessed to ludicrous deeds suggested by the inquisitors. Having “proven” their case, the inquisitors sent their prisoner to be executed (typically in the way of most heretics at the time, burning at the stake, though some were hung or crushed by rocks, etc.). If the accused party held out and insisted on their innocence, they were considered unrepentant and executed anyway (or they died from the extended torture and imprisonment). It truly was a dark and troubling time in history.

With the Enlightenment came a reprieve. Witchcraft was largely relegated to superstition though belief certainly persisted, especially in more remote and rural areas. In the mid-1800s came the “Spiritualism” movement which was mostly concerned with contacting the dead. Occult and esoteric interest was starting to see a revival and became more prominent with figures like Aleister Crowley who was often accused of devil worship.

Amidst this general revival of spiritual and esoteric practices, an English man by the name of Gerald Gardner claimed to have been a guest of a secret coven of the “Witch-Cult”. Gardner fancied himself an amateur anthropologist and was heavily influenced by Margaret Murray’s proposed theory of secret fertility cults continuing pagan practices in Europe. Murray’s work was popular in her time but is generally considered to be seriously flawed by today’s academic standards. Gardner likewise wasn’t known for his rigid adherence to things like “facts” and “truth”. Regardless, this confluence of interest in pagan rituals of Europe, and Britain in particular, fueled Gardner’s “Wicca” movement. The historical understanding of witches as innocent people persecuted by religious hysteria fell by the wayside as this new idea of secret covens that kept alive ancient pagan practices gained, if not acceptance, at least interest.

Since Gardner, Wicca has grown, changed, and adapted. There have been many interpretations and reimaginings that stem from individual practices, adoption of historical pagan rituals, and mixing both modern sensibilities and eastern philosophy into different systems. There is no “correct” way to be a Wiccan practitioner. See the section below on “Key Concepts” for some general ideas you might come across if you’re looking to practice Wicca or another form of witchcraft.

Folk Practices

One form of witchcraft exists in much the same form it did centuries earlier in parts of Europe; a tradition passed down the matrilineal line that blends folk medicine, curses, fortune telling, and rituals. Vice’s Broadly takes a look at contemporary witches in Romania in this short documentary:

Magic practices in Africa (and other parts of the world) are sometimes labeled as witchcraft but more appropriately fall under the label of folk traditions, native beliefs, or religions as opposed to the western idea of witchcraft. Witch doctors may better be understood as local medicine or wise men/women. Like their European counterparts, the label “witch” was applied to deride and demonize their status in the community or in contrast to the “civilized” Christian faith. This of course was increasingly common during the process of colonization.

Other Details

Most witchcraft is divided, both by its critics and practitioners, between black (evil) and white (good) magic. The distinction is generally thought of along the lines of destructive or constructive, good or bad. Curses, hexes, and negative effects fall under the former while healing, charms, and prayers fall into the latter. Some witches choose to use exclusively black or white while others mix magics freely depending on their desired results. Historically, black magic was associated with making a pact with the devil who granted such powers. More often than not, such charges of satanic witchcraft were fabricated. Wiccans don’t worship Satan, though their “Horned God” is often mistaken for a devil figure. Certain satanists may also describe themselves as witches and/or practice “witchcraft”.

Witchcraft is often associated with women though men have, and do, practice the craft. Many, many more women were falsely charged with practicing witchcraft than men though men were certainly not immune from such accusations. “Warlock” is sometimes used to distinguish a male witch from his female counterparts but “witch” is generally accepted as a non-gendered title in modern practice.

Key Concepts

The Witches’ Sabbath or Black Sabbath: These are relatively modern terms used to describe a gathering of witches, typically for nefarious purposes, that featured revelry, rituals, heresy, hedonism, and sometimes a visit from Satan himself. Spanish painter Francisco Goya portrayed a Witches’ Sabbath in two of his most famous works, one from his series of “Black Paintings”.

Walpurgis Night: A celebration of Saint Walpurgis who was called upon to protect against witchcraft and demons. The tradition of lighting bonfires and calling upon the saint was in response to supposed gatherings of witches on the same night. It has been “reclaimed” in a way by some modern satanists, pagans, witches, and Wiccans. It also features prominently in the Faust myth and in the novel The Master and Margarita, which itself is loosely based on the legend.

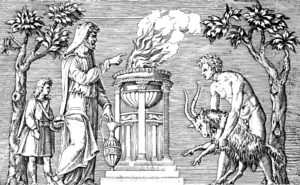

Wiccan Gods: The most common gods in the Wiccan faith are a male “Horned God” and a female “Goddess” representing a dualistic polytheism. This male/female dichotomy played a large role in early iterations of the faith. The Horned God, sometimes called “Cernunnos” drawing from ancient Celtic depictions of a similar deity, is associated with the sun, animals, the woods, and nature in general. He shares some features with the Greek gods Pan or Sylvanus. The Goddess figure can be represented by a “mother goddess” or “Gaia” as the mother of all creation. Also common is the “triple goddess”, a maid, mother, and crone each represent a facet of the same goddess as well as three stages in a woman’s life. This imagery evokes another common patron deity, Hecate, the ancient Greek goddess of magic and witchcraft who is depicted with three faces, three connected bodies, or three female figures. In some Wiccan and neopagan practices, one can choose almost any god, goddess, or spirit from myth or history as one’s “patron deity” to pray to and give offerings.

The Rule of Three: A concept popularized by film and television depictions of witches and derived from early forms of Wicca, the “Rule of Three” is that whatever spell or hex a person casts comes back on them threefold. It functions as a type of karma that dissuades people from trying to cause harm to others.

Wiccan Rede: A guiding principle from early Wiccan writings that closely resembles Aleister Crowley’s “Do what thou wilt” imperative. Gardner had met and was familiar with Crowley so the parallel is unsurprising. The Wiccan Rede has many iterations but the sentiment remains the same. Early Wiccan adopter and author Doreen Valiente’s version is one of the more common:

An ye harm none, do what ye will

Essentially, as long as you’re not hurting anyone, or anything, you’re free to do what you like.

Wheel of the Year: This is another very common Wiccan element that draws on many other pagan traditions that varies quite a bit among individuals and sects. A year is depicted as a wheel and is most often divided into eight equal parts, each “spoke” on the wheel representing a holiday or “sabbat”. They usually consist of the two equinoxes (Ostara for the vernal, Mabon for the autumnal), two solstices (Yuletide for winter, Litha for summer), and four based on Celtic tradition (Samhain, Imbolc, Beltane, and Lughnasadh). Each holiday has different rituals, festivals, or traditions based on the time of year and its meaning. For Wiccans in the southern hemisphere, the dates are typically moved six months to correspond to the appropriate season since the holidays aren’t about a particular date, instead reflecting what is going on in nature.

![]() For those interested in practicing witchcraft, if you’re attracted to nature, a connection with mother earth, and empowering yourself with rituals revolving around these, you’ll likely be at home with Wicca. If your wardrobe is all black, you enjoy satanic imagery, and are attracted exclusively to black magic, a form of satanism is most likely what you’re looking for. Both Satanists and Wiccans may describe themselves as “witches” and what they do as “witchcraft” regardless. If you can’t decide between the two, feel free to mix and match to your heart’s content. One of the advantages of occult systems is they cater to individual expression and exploration as opposed to strict dogma. I of course don’t advocate violence in any way towards human or animal so please don’t be inspired to practice any of the bloodier aspects of these traditions. Regardless of where your craft takes you, be safe and be respectful to all life.

For those interested in practicing witchcraft, if you’re attracted to nature, a connection with mother earth, and empowering yourself with rituals revolving around these, you’ll likely be at home with Wicca. If your wardrobe is all black, you enjoy satanic imagery, and are attracted exclusively to black magic, a form of satanism is most likely what you’re looking for. Both Satanists and Wiccans may describe themselves as “witches” and what they do as “witchcraft” regardless. If you can’t decide between the two, feel free to mix and match to your heart’s content. One of the advantages of occult systems is they cater to individual expression and exploration as opposed to strict dogma. I of course don’t advocate violence in any way towards human or animal so please don’t be inspired to practice any of the bloodier aspects of these traditions. Regardless of where your craft takes you, be safe and be respectful to all life.

Outside Resources

![]() For a general overview of witches and witchcraft throughout history with an emphasis on their portrayal in fiction and media, the Youtube channel In Praise of Shadows has produced an excellent three part video essay:

For a general overview of witches and witchcraft throughout history with an emphasis on their portrayal in fiction and media, the Youtube channel In Praise of Shadows has produced an excellent three part video essay:

Part 1:

Part 2:

Part 3:

Museums

Museum of Witchcraft and Magic – Located in Cornwall, England, this museum has a long and interesting history in addition to many quality exhibits and resources.

Salem, Massachusetts – A town made famous with the trial and execution of nineteen accused witches, Salem has capitalized on its morbid history in the form of tourism.

General Witch Related Tourism Info

Galdrasyning – The Museum of Icelandic Sorcery and Witchcraft (home of the infamous “necropants” among other interesting artifacts):

Press release and images:

http://www.galdrasyning.is/press/

![]()

Bibliography and Recommended Reading

The Commissioners of the Public Records of the Kingdom [Great Britain]. Ancient Laws and Institutes of England. Great Britain, 1840. https://books.google.com/books?id=9FYtAQAAMAAJ&pg=PA2#v=onepage&q&f=false

(1991). Law-code of King Alfred the Great (Doctoral thesis). https://doi.org/10.17863/CAM.15910

Ezzy, Douglas. “The Commodification of Witchcraft.” Australian Religion Studies Review, vol. 14, no. 1, 2001, pp. 31-44.

Frazer, James. The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion. Abridged ed, Penguin Books, 1996.

Hutton, Ronald. “Paganism and Polemic: The Debate over the Origins of Modern Pagan Witchcraft.” Folklore, vol. 111, no. 1, 2000, pp. 103–117. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1260981.

Jencson, Linda. “Neopaganism and the Great Mother Goddess: Anthropology as Midwife to a New Religion.” Anthropology Today, vol. 5, no. 2, 1989, pp. 2–4. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3033137.

LaVey, Anton Szandor. The Satanic Bible. Avon Books, 2005.

Levack, Brian P., editor. The Witchcraft Sourcebook. Routledge, 2004.

“Medieval Sourcebook: Witchcraft Documents [15th Century].” Internet History Sourcebooks Project, 1996, sourcebooks.fordham.edu/source/witches1.asp.

Partridge, Christopher, editor. The Occult World. Routledge, 2016.

Simpson, Jacqueline. “Margaret Murray: Who Believed Her, and Why?” Folklore, vol. 105, 1994, pp. 89–96. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1260633.

Shumaker, Wayne. The Occult Sciences in the Renaissance: A Study in Intellectual Patterns. University of California Press, 1979.

Waldron, David. “Witchcraft for Sale! Commodity vs. Community in the Neopagan Movement.” Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions, vol. 9, no. 1, Aug. 2005, pp. 32–48.